![The Dung Beetle and Me [Guest Post + Giveaway]](https://companyoverdrive.cdn.overdrive.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/2025-the-dung-beetle-and-me-blog-feature-image.jpg)

The Dung Beetle and Me [Guest Post + Giveaway]

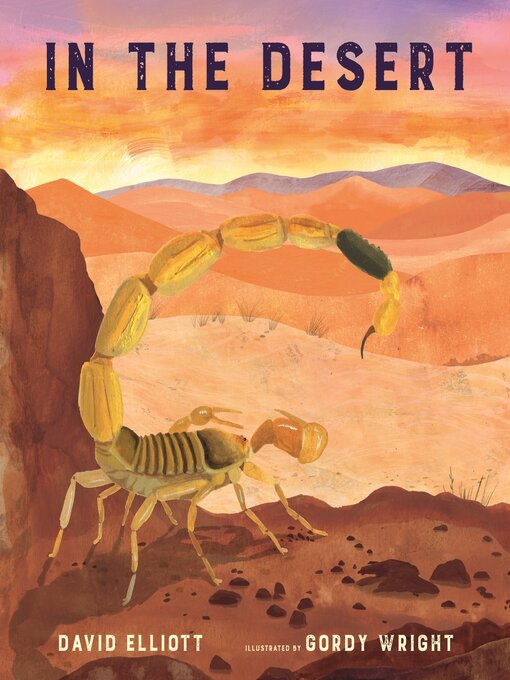

By: David Elliott, Author of In the Desert

Animals. I live in rural New Hampshire. Last spring, a black bear strolled across our yard as if he owned the place. (And us!) One early autumn morning a year or so ago, I surprised a huge bull moose in the field behind our house. (More accurately, he surprised me.) From our bedroom window, I have watched an owl swoop down to capture a vole that thought it was safe under a thick blanket of snow. And just last night, the coyotes were screaming like lovelorn banshees in the woods behind us. But the animals in our neighborhood are not limited to the feral. Our town’s annual fall festival wouldn’t be the same without its oxen pull. And every Friday, our neighbor delivers a dozen eggs thanks to her flock of backyard hens. From the vixen trotting across our lower field to the flock of sheep 4-H kids show at the local fair, animals are a part of our everyday life here.

In the beginning, my goal was not to teach kids about the owl (On the Wing) or the bear (In the Woods) or even the tyrannosaur (In the Past). Rather, it was to allow the poems to demonstrate for young readers the unlimited possibilities inherent in the same language they use to complain about their homework or ask what’s for dinner. Some of the poems are playful. Some philosophical. Some make use of five- or even six-syllable words. Some are short. Very short. (In the Woods includes “The Moose,” which reads in its entirety, “Ungainly, / mainly.”) But whatever their style or point of view or length, the poems were only a vehicle to demonstrate the beauty, the spirit, the buoyancy of English. I would have been just as happy to write about heroes of the Punic Wars or Norse gods or kinds of pie. Especially pie.

As I worked on each subsequent book in the series, my interest in the language remained strong, but I found my focus expanding. As I read and wrote about the porcupine (In the Woods) or the sea turtle (In the Sea) or the dragonfly (At the Pond), I was beginning to embrace, however unconsciously, writer/biologist Marc Bekoff’s admonition to “remember that animals are not mere resources for human consumption. They are splendid beings in their own right, who have evolved alongside us as co-inheritors of all the beauty and abundance of life on this planet.” In other words, the animals were no longer just the bobbins around which I wanted to spin the language, but creatures to be admired, to be respected, to be held in awe.

This was especially evident when working on In the Desert. I still don’t know why animals of the Sahara should have moved me so. Maybe it’s because in spite of the extreme adversity of their environment—the searing daytime temperatures, the freezing nights, the lack of water—they go about the task of living their lives as routinely as Holsteins on a well-tended farm. But I also love their subversive qualities hiding under the most frightening physiognomies or repellent habits.

Take, for example, the deathstalker scorpion. (A sentence, by the way, I never thought I’d write.) Two inches long, its stinging tail curls over its back like a scythe on the shoulder of the Grim Reaper. With its eight creepily articulated legs, its Edward Scissorhands pincers, and its sickly yellow pallor, the scorpion is about as far from a human’s idea of cuddly as it could possibly be. And let’s not forget about its venom—one of the most toxic in the world. Yet in that same venom lives a substance called chlorotoxin. Researchers have learned that chlorotoxin is a powerful weapon against glioma, an aggressive brain cancer. Before writing In the Desert, the thought of this arachnid scuttling across the desert would have repulsed me. But writing about her has taught me to step back and consider just how much I don’t know. I think about the animals that we have driven to extinction. The golden toad. The Caspian tiger. The Carolina parakeet. How many of them held secrets that, once revealed, might have saved lives, or fed the hungry, or saved the planet from the ravages of climate change?

Every creature, from the apatosaurus to the pollywog, has something to teach. But none is more astonishing than the dung beetle. Scarabaeus sacer spends its life cleaning the desert by rolling the waste of other animals into marble-sized balls. In order to get back to its nest with the mini-globe of poop—which, by the way, it eats—the dung beetle turns its attention toward the heavens and, as incredible as it may seem, takes a mental snapshot of the Milky Way, which it then uses to navigate its way back home. The dung beetle: the lowliest creature with the (literally) highest aspirations.

Each night before bed, I take Queequeg, our rescue terrier from the streets of Houston, out into the yard. I stand in the dark and look up at the New Hampshire sky, and if the night is clear, as it often is, the wide furrow of the Milky Way stretches across the heavens. I think of the tiny dung beetle on the other side of the planet and do my best to take a mental picture of our (the beetle’s and my) galaxy. But of course, it’s impossible. And yet, there is the scarab, its brain no larger than a sesame seed, rolling its balls of waste, taking pictures, finding its way home.

Authors often receive letters from readers saying how the writer’s work has changed their lives. Nothing could be more gratifying. But it’s also true that writing can change the author. Writing these books has helped me acknowledge that I represent just one of the 8.7 million species with whom we have co-inherited, to borrow Bekoff’s term, the earth, that each of us has developed skills and talents appropriate to its kind, and that each species has its place, not in a hierarchical list of who’s best, but in an interconnected web of infinite wonder. Working on the series has reminded me of my humble place in that web. What a relief it is to have laid down the heavy burden of dominion.

The dung beetle comforts me and brings me closer to the sacred. My hope now is that the books in the series will help to steer young readers into sharing that feeling.

The Dung Beetle (from In the Desert)

How easy

to make

fun of

you. That

rolling

thing you

do? Most

would find

appalling.

How strange

your mean

and humble

calling. No

one would

guess your

lowly work’s

determined

by the

stars. How

elegant!

How surprising!

How celestial

you are!

About the Author:

In addition to In the Desert, David Elliott is the author of many other children’s books, including What the Grizzly Knows, Finn Throws a Fit, and the animal poetry series including On the Farm, In the Wild, In the Sea, and On the Wing. He lives in New Hampshire with his wife and son and their bearded collie, Psyche.

GIVEAWAY TIME!

GIVEAWAY TIME!

Are you looking for a fresh way to spark classroom conversations? Look no further – we’re giving away a collection David Elliott’s poetry books, including In the Desert and some of the other titles mentioned here.

Head over to our Instagram to enter, and don’t miss these key steps:

- Make sure you’re following @sorareadingapp on Instagram

- Tag a teacher friend in the comments

- Share this post to your stories for an extra entry

Giveaway runs through Sept. 4 – Don’t miss out!

Browse blog and media articles

Public Library Training

K-12 Library Training